History

View all in History

Odiani Clan: A Yoruba Enclave in the Heart of Anioma

By Adim Abuah on February 9, 2026

𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

The history of Anioma communities is inseparable from the patterns of migration, cultural

intersections and shifting identities that have shaped western Nigeria. Among the lesser

known but historically rich communities within this landscape is the Odiani, or Olukumi

clan, located in Aniocha North of Delta State. Odiani clan, also known as the Olukumi people

represent a case of cultural synthesis rooted in a Yoruboid past, extended through Edo contact

and ultimately settled within an Igbo-speaking region. Their language, traditions and oral memory

preserve a distinctive identity that stands apart from their Anioma neighbors, yet remains

embedded in the shared historical experience of the region.

This article examines the formation of the Odiani clan from a historiographical perspective,

placing it within the wider framework of Yoruba-Benin-Anioma interaction. It draws on oral

histories, linguistic research and local cultural accounts to reconstruct the evolution of the

Odiani people. The focus is not solely on tracing their origins, but also on understanding

the layered dimensions of their kingship, religious life, language, inter-communal ties and

cultural memory. Through this lens, the Odiani are presented not as cultural anomalies,

but as a living example of historical fusion within the Anioma region

𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐎𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐌𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

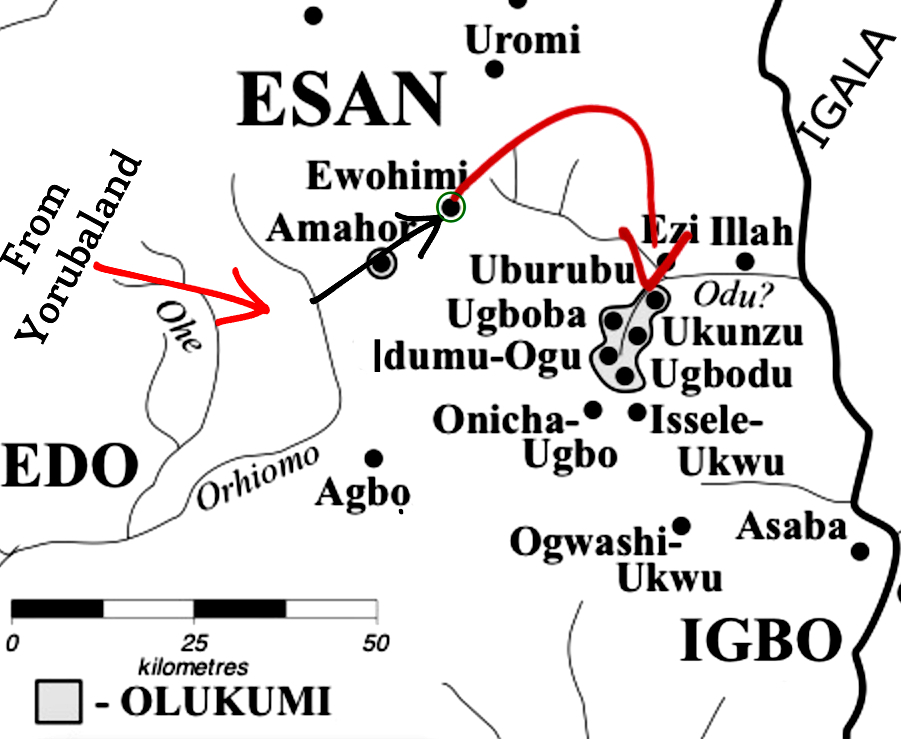

The communities of the Odiani clan trace their ancestry to Yoruba-speaking migrants from

Ife, Owo and Akure, who moved eastward over several centuries. Oral traditions record

that the earliest settlement, Ugbodu, was founded between the twelfth and fifteenth

centuries by a group led by Kokoroko (also called Adetola), a figure of Akure origin.

According to oral custodians in Ugbodu, these early migrants passed through Benin during

the Ogiso period, encountered internal palace conflict and moved on to Esan territory,

specifically Ewohimi. Conflict there again prompted their eastward movement, ending with

the establishment of Ugbodu. This settlement became the central point from which other

Odiani communities emerged.

Subsequent waves of migration introduced new figures and groups into the region. A

group from Owo, remembered as Ologun Uja, arrived in the seventeenth century and

assisted Ugbodu during conflicts with Esan neighbors. Their contributions led to the

institution of a distinct warrior chieftaincy in the Ugbodu sociopolitical structure.

Meanwhile, another early settlement, Ukwu Nzu (historically known as Eko Ẹfun, or “chalk

camp”), was founded by a leader named Ogbe or Ugbe, said to have originated from Ile-Ife.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Odiani clan had expanded into a network

of seven settlements: Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu, Ubulubu, Idumu Ogo, Ugboba, Ogodor and

Anioma village. Ubulubu and Idumu Ogo emerged as extensions of Ugbodu and Ukwu Nzu.

Ugboba and Ogodor were later additions, reportedly influenced by Edo migrants, while

Anioma was established by migrants from Ubulubu. These communities occupy a small but

historically significant belt in western Anioma, near the western bank of the Niger.

𝐄𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐅𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬

The genealogies of the Odiani towns are maintained through lineage memory and oral

performance. Kokoroko, the Akure-origin founder of Ugbodu, and Oligbo, another pioneer

associated with the Isile group, are foundational names in the clan’s narrative. The Isile

people, identified as early settlers or strangers, joined the Ugbodu founders and are

sometimes credited with introducing the term Olukumi. Ugbodu retains a quarter named

Ologoza, commemorating the Owo warriors who defended the town in the late seventeenth

century.

Other towns trace their leadership back to identifiable figures as well. Ugbe of Ife is

credited with founding Ukwu Nzu. Ubulubu, founded around 1800 by migrants from

Ugbodu and Ukwu Nzu, developed a different system of governance led by a council of

elders (Okpalabisi) rather than a hereditary monarchy. Ugboba and Ogodor are understood

to have Edo heritage, while Anioma remained politically tied to Ubulubu.

Across the Odiani towns, leadership traditions reflect a convergence of Yoruba, Edo and

Igbo influences. Ugbodu’s monarch bears the title Ọlọza, and earlier holders of the title

carried Yoruba names. Over time, Edo and Igbo names began to appear in the chieftaincy,

reflecting both external influence and internal adaptation. Ukwu Nzu adopted the title Obi,

and its ruler, Ogoh I, ascended the throne in the 1970s. All Odiani communities maintain

advisory councils composed of elders selected from senior lineages.

Religious authority is also embedded in lineage structures. In Ugbodu, the primary

ancestral and land deities are Alẹ-Ugbodu and Alẹ-Ighare. In Ukwu Nzu, royal

enthronement is tied to the Ihongbuda shrine, with specific ritual items passed from one

ruling house to the next. These practices illustrate a religious system shaped by multiple

historical layers, with Yoruba, Edo and Igbo elements coexisting

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐎𝐥𝐮𝐤𝐮𝐦𝐢 𝐋𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞: 𝐄𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐬

Olukumi is a Yoruboid language and functions as the primary marker of Odiani identity. The

name itself, Olukumi, means “my friend” or “my confidant” in Yoruba, underscoring its

origin in Yoruba migration. Linguistic studies place Olukumi within the Niger-Congo family,

closely related to Yoruba, and note similarities with languages such as Itsekiri.

Today, Olukumi survives in three of the seven Odiani towns: Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu and

Ubulubu. The remaining four have adopted Enuani Igbo as their dominant language, with

only vestigial traces of Olukumi. Even within the core-speaking towns, Olukumi shows

signs of decline. In Ugbodu, it is still spoken fluently by elders and used in community

rituals. In Ukwu Nzu and Ubulubu, Olukumi is heavily influenced by Igbo vocabulary and

syntax.

Olukumi is not taught in schools and is not widely written, but efforts have been made to

preserve it. The Ugbodu traditional council has supported the development of an Olukumi

English dictionary and an Olukumi translation of the New Testament. Some churches

conduct services and prayers in Olukumi, and youth programs have been introduced to

encourage oral fluency. Despite these efforts, the language remains endangered,

particularly in the face of dominant Igbo usage in surrounding communities.

The bilingualism of the Odiani people once carried symbolic prestige. Speaking both

Olukumi and Igbo indicated cultural rootedness and regional adaptability. Today, that

prestige is being redefined through conscious preservation, identity discourse and

linguistic revival initiatives

𝐂𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞, 𝐅𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐁𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐟𝐬

Cultural life in the Odiani communities follows a blended path, shaped by Yoruba

foundations, Benin contact and Igbo regional norms. Festivities such as the New Yam

Festival are celebrated in all towns, with accompanying rituals like Ifejioku (yam sacrifice)

reflecting regional practice. Ancestral veneration, land deity observances and seasonal

rites remain integral to community life.

Funeral practices provide a key example of cultural variation. In some Odiani communities,

burial rites extend over seven days, more in line with Edo or Esan patterns, as opposed to

the four-day structure common in most Igbo communities. Marriage and title-taking

customs, on the other hand, follow the Anioma pattern, with ceremonies conducted in Igbo

and family negotiations rooted in Igbo lineage systems.

Christianity has become the dominant religion in the region, particularly Roman

Catholicism and Anglicanism. Churches have played an active role in cultural preservation,

introducing Olukumi hymnals, incorporating Olukumi phrases in sermons and encouraging

youth participation in cultural activities.

Although no distinct Olukumi masquerade systems have survived in full, symbolic

remnants exist in seasonal festivals, music and oral performance. Traditional dress,

especially white and colorful wrappers known as akwaocha, is shared with the wider

Anioma region

𝐆𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐀𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

Historically, each Odiani town operated as an autonomous polity. The monarch and senior

elders managed political and ritual affairs. Ugbodu’s Oloza, Ukwu Nzu’s Obi and Ubulubu’s

elder council represent the three core governing systems of the clan. Hereditary

chieftaincy remains strong in some towns, while others use seniority-based systems

adapted from Igbo political logic.

Under British colonial rule, the Odiani villages were grouped into a single Native Authority

centered in Ukwu Nzu. This realignment followed the 1904 Ekumeku conflict, in which

colonial administrators shifted the regional seat of governance from Ugbodu to Ukwu Nzu.

Despite this change, Ugbodu remains culturally regarded as the senior town. After

independence, all Odiani towns were incorporated into the Aniocha North Local

Government Area.

Today, governance in Odiani communities reflects the broader Anioma structure.

Monarchs operate alongside elected officials, elders’ councils continue to play advisory

roles and traditional rites coexist with modern administration. The Odiani retain internal

cohesion through festivals, family alliances and linguistic ties, even as they participate

fully in the wider political life of Anioma.

𝐎𝐥𝐮𝐤𝐮𝐦𝐢 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐈𝐠𝐛𝐨-𝐒𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐓𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐬: 𝐀 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧

The division between Olukumi-speaking and Igbo-speaking Odiani towns illustrates a

broader historical dynamic. Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu and Ubulubu preserve the Olukumi

language and certain Yoruba cultural features. In contrast, Ugboba, Idumu Ogo, Ogodor

and Anioma village have adopted Enuani Igbo entirely. These towns were influenced by

later migrations and cultural assimilation from neighboring Igbo and Esan populations.

Despite linguistic differences, cultural continuity remains. Dress, festivals, age-grade

systems and community structures are shared across the Odiani towns. Ritual and

ceremonial differences exist, but they are integrated into the overall Anioma cultural

rhythm. Some practices, such as extended funeral durations or ancestral titles, preserve

the memory of Odiani’s distinct past, even within the larger Igbo-speaking context

𝐎𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐌𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐲

Odiani identity is preserved through oral history, family memory and community ritual.

Elders recount the migration from Yorubaland through Benin and Esan, and the eventual

settlement of Ugbodu. These accounts are reinforced by cultural performances and public

ceremonies. Books such as George Nkemnacho’s “Olukumi Kingdom” and articles in local

newspapers have documented the history of the Odiani people, bringing scholarly and

public attention to their heritage.

Today, community memory is also curated through digital media. Facebook pages, cultural

blogs and local forums share Odiani stories, songs and language lessons. Community

events emphasize traditional knowledge, and some families maintain oral genealogies

tracing their lineages to the original Yoruba migrants.

This oral tradition is not fixed but dynamic. It accommodates changes in language, religion

and governance while maintaining the core narrative of Odiani as a Yoruboid-speaking

people who adapted to a changing regional environment. The Odiani case affirms that

cultural identity is not singular, but layered and continuously negotiated

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

The history of the Odiani clan offers a window into the processes of migration, contact and

adaptation that define Anioma. Emerging from Yorubaland, shaped by Benin encounter and

embedded in an Igbo-speaking region, the Odiani illustrate how historical identities are

formed and transformed across generations.

They are not simply Yoruba exiles nor Igbo converts, but a community that carries

elements of both, reshaped by place and time. Olukumi, their language, remains a fragile

but vital marker of this history. Their governance structures, religious practices and

festivals reflect a shared heritage that is at once distinctive and interconnected with the

broader Anioma experience.

Understanding the Odiani in this way enhances our appreciation of Anioma as a frontier

region where identity is not fixed, but continuously constructed through encounter,

negotiation and cultural memory.

𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬

Aluko, B. (2010, 2015, 2022). Olukumi people of Delta State and their Yoruba origins.

Nigerian Tribune (various reprints and online editions).

Bamgbose, A. A. (1966). A grammar of Yoruba. Cambridge University Press.

(Referenced for comparative Yoruboid linguistic classification relevant to Olukumi.)

Beier, H. U. (1953). Notes on the Olukumi people of Western Nigeria.

(Unpublished field notes and linguistic observations, cited in later ethnolinguistic

studies.)

Esogbue, E. (2016). Anioma history and ethnographic notes.

(Online cultural essays and regional history blog posts.)

Nkemnacho, G. (2024). Olukumi Kingdom: History, language and identity of the Odiani

people.

Self-published monograph, Ugbodu.

Nwoye, G. (2008). Language contact and shift in border communities of Delta State.

Journal of West African Linguistics, 35(2), 45–68.

Ohadike, D. C. (1994). Anioma: A social history of the Western Igbo people. Ohio

University Press.

Talbot, P. A. (1926). The peoples of Southern Nigeria.

Oxford University Press.

(Referenced for early colonial observations of Anioma and neighboring Edo–Igbo frontier

zones.)

Ugbodu Traditional Council. (2022). Olukumi–English Dictionary Project and New

Testament Translation.

Community publication and launch materials.

Ukwu-Nzu Palace Records. (1974). Coronation and lineage records of the Obi of Ukwu

Nzu.

Unpublished palace archives.

Oral interviews and community accounts from:

• Ugbodu

• Ukwu-Nzu

• Ubulubu

• Idumu-Ogo

• Ugboba

• Ogodor

The history of Anioma communities is inseparable from the patterns of migration, cultural

intersections and shifting identities that have shaped western Nigeria. Among the lesser

known but historically rich communities within this landscape is the Odiani, or Olukumi

clan, located in Aniocha North of Delta State. Odiani clan, also known as the Olukumi people

represent a case of cultural synthesis rooted in a Yoruboid past, extended through Edo contact

and ultimately settled within an Igbo-speaking region. Their language, traditions and oral memory

preserve a distinctive identity that stands apart from their Anioma neighbors, yet remains

embedded in the shared historical experience of the region.

This article examines the formation of the Odiani clan from a historiographical perspective,

placing it within the wider framework of Yoruba-Benin-Anioma interaction. It draws on oral

histories, linguistic research and local cultural accounts to reconstruct the evolution of the

Odiani people. The focus is not solely on tracing their origins, but also on understanding

the layered dimensions of their kingship, religious life, language, inter-communal ties and

cultural memory. Through this lens, the Odiani are presented not as cultural anomalies,

but as a living example of historical fusion within the Anioma region

𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐎𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐌𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

The communities of the Odiani clan trace their ancestry to Yoruba-speaking migrants from

Ife, Owo and Akure, who moved eastward over several centuries. Oral traditions record

that the earliest settlement, Ugbodu, was founded between the twelfth and fifteenth

centuries by a group led by Kokoroko (also called Adetola), a figure of Akure origin.

According to oral custodians in Ugbodu, these early migrants passed through Benin during

the Ogiso period, encountered internal palace conflict and moved on to Esan territory,

specifically Ewohimi. Conflict there again prompted their eastward movement, ending with

the establishment of Ugbodu. This settlement became the central point from which other

Odiani communities emerged.

Subsequent waves of migration introduced new figures and groups into the region. A

group from Owo, remembered as Ologun Uja, arrived in the seventeenth century and

assisted Ugbodu during conflicts with Esan neighbors. Their contributions led to the

institution of a distinct warrior chieftaincy in the Ugbodu sociopolitical structure.

Meanwhile, another early settlement, Ukwu Nzu (historically known as Eko Ẹfun, or “chalk

camp”), was founded by a leader named Ogbe or Ugbe, said to have originated from Ile-Ife.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Odiani clan had expanded into a network

of seven settlements: Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu, Ubulubu, Idumu Ogo, Ugboba, Ogodor and

Anioma village. Ubulubu and Idumu Ogo emerged as extensions of Ugbodu and Ukwu Nzu.

Ugboba and Ogodor were later additions, reportedly influenced by Edo migrants, while

Anioma was established by migrants from Ubulubu. These communities occupy a small but

historically significant belt in western Anioma, near the western bank of the Niger.

𝐄𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐅𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬

The genealogies of the Odiani towns are maintained through lineage memory and oral

performance. Kokoroko, the Akure-origin founder of Ugbodu, and Oligbo, another pioneer

associated with the Isile group, are foundational names in the clan’s narrative. The Isile

people, identified as early settlers or strangers, joined the Ugbodu founders and are

sometimes credited with introducing the term Olukumi. Ugbodu retains a quarter named

Ologoza, commemorating the Owo warriors who defended the town in the late seventeenth

century.

Other towns trace their leadership back to identifiable figures as well. Ugbe of Ife is

credited with founding Ukwu Nzu. Ubulubu, founded around 1800 by migrants from

Ugbodu and Ukwu Nzu, developed a different system of governance led by a council of

elders (Okpalabisi) rather than a hereditary monarchy. Ugboba and Ogodor are understood

to have Edo heritage, while Anioma remained politically tied to Ubulubu.

Across the Odiani towns, leadership traditions reflect a convergence of Yoruba, Edo and

Igbo influences. Ugbodu’s monarch bears the title Ọlọza, and earlier holders of the title

carried Yoruba names. Over time, Edo and Igbo names began to appear in the chieftaincy,

reflecting both external influence and internal adaptation. Ukwu Nzu adopted the title Obi,

and its ruler, Ogoh I, ascended the throne in the 1970s. All Odiani communities maintain

advisory councils composed of elders selected from senior lineages.

Religious authority is also embedded in lineage structures. In Ugbodu, the primary

ancestral and land deities are Alẹ-Ugbodu and Alẹ-Ighare. In Ukwu Nzu, royal

enthronement is tied to the Ihongbuda shrine, with specific ritual items passed from one

ruling house to the next. These practices illustrate a religious system shaped by multiple

historical layers, with Yoruba, Edo and Igbo elements coexisting

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐎𝐥𝐮𝐤𝐮𝐦𝐢 𝐋𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞: 𝐄𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐬

Olukumi is a Yoruboid language and functions as the primary marker of Odiani identity. The

name itself, Olukumi, means “my friend” or “my confidant” in Yoruba, underscoring its

origin in Yoruba migration. Linguistic studies place Olukumi within the Niger-Congo family,

closely related to Yoruba, and note similarities with languages such as Itsekiri.

Today, Olukumi survives in three of the seven Odiani towns: Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu and

Ubulubu. The remaining four have adopted Enuani Igbo as their dominant language, with

only vestigial traces of Olukumi. Even within the core-speaking towns, Olukumi shows

signs of decline. In Ugbodu, it is still spoken fluently by elders and used in community

rituals. In Ukwu Nzu and Ubulubu, Olukumi is heavily influenced by Igbo vocabulary and

syntax.

Olukumi is not taught in schools and is not widely written, but efforts have been made to

preserve it. The Ugbodu traditional council has supported the development of an Olukumi

English dictionary and an Olukumi translation of the New Testament. Some churches

conduct services and prayers in Olukumi, and youth programs have been introduced to

encourage oral fluency. Despite these efforts, the language remains endangered,

particularly in the face of dominant Igbo usage in surrounding communities.

The bilingualism of the Odiani people once carried symbolic prestige. Speaking both

Olukumi and Igbo indicated cultural rootedness and regional adaptability. Today, that

prestige is being redefined through conscious preservation, identity discourse and

linguistic revival initiatives

𝐂𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞, 𝐅𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐁𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐟𝐬

Cultural life in the Odiani communities follows a blended path, shaped by Yoruba

foundations, Benin contact and Igbo regional norms. Festivities such as the New Yam

Festival are celebrated in all towns, with accompanying rituals like Ifejioku (yam sacrifice)

reflecting regional practice. Ancestral veneration, land deity observances and seasonal

rites remain integral to community life.

Funeral practices provide a key example of cultural variation. In some Odiani communities,

burial rites extend over seven days, more in line with Edo or Esan patterns, as opposed to

the four-day structure common in most Igbo communities. Marriage and title-taking

customs, on the other hand, follow the Anioma pattern, with ceremonies conducted in Igbo

and family negotiations rooted in Igbo lineage systems.

Christianity has become the dominant religion in the region, particularly Roman

Catholicism and Anglicanism. Churches have played an active role in cultural preservation,

introducing Olukumi hymnals, incorporating Olukumi phrases in sermons and encouraging

youth participation in cultural activities.

Although no distinct Olukumi masquerade systems have survived in full, symbolic

remnants exist in seasonal festivals, music and oral performance. Traditional dress,

especially white and colorful wrappers known as akwaocha, is shared with the wider

Anioma region

𝐆𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐀𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

Historically, each Odiani town operated as an autonomous polity. The monarch and senior

elders managed political and ritual affairs. Ugbodu’s Oloza, Ukwu Nzu’s Obi and Ubulubu’s

elder council represent the three core governing systems of the clan. Hereditary

chieftaincy remains strong in some towns, while others use seniority-based systems

adapted from Igbo political logic.

Under British colonial rule, the Odiani villages were grouped into a single Native Authority

centered in Ukwu Nzu. This realignment followed the 1904 Ekumeku conflict, in which

colonial administrators shifted the regional seat of governance from Ugbodu to Ukwu Nzu.

Despite this change, Ugbodu remains culturally regarded as the senior town. After

independence, all Odiani towns were incorporated into the Aniocha North Local

Government Area.

Today, governance in Odiani communities reflects the broader Anioma structure.

Monarchs operate alongside elected officials, elders’ councils continue to play advisory

roles and traditional rites coexist with modern administration. The Odiani retain internal

cohesion through festivals, family alliances and linguistic ties, even as they participate

fully in the wider political life of Anioma.

𝐎𝐥𝐮𝐤𝐮𝐦𝐢 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐈𝐠𝐛𝐨-𝐒𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐓𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐬: 𝐀 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧

The division between Olukumi-speaking and Igbo-speaking Odiani towns illustrates a

broader historical dynamic. Ugbodu, Ukwu Nzu and Ubulubu preserve the Olukumi

language and certain Yoruba cultural features. In contrast, Ugboba, Idumu Ogo, Ogodor

and Anioma village have adopted Enuani Igbo entirely. These towns were influenced by

later migrations and cultural assimilation from neighboring Igbo and Esan populations.

Despite linguistic differences, cultural continuity remains. Dress, festivals, age-grade

systems and community structures are shared across the Odiani towns. Ritual and

ceremonial differences exist, but they are integrated into the overall Anioma cultural

rhythm. Some practices, such as extended funeral durations or ancestral titles, preserve

the memory of Odiani’s distinct past, even within the larger Igbo-speaking context

𝐎𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐌𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐲

Odiani identity is preserved through oral history, family memory and community ritual.

Elders recount the migration from Yorubaland through Benin and Esan, and the eventual

settlement of Ugbodu. These accounts are reinforced by cultural performances and public

ceremonies. Books such as George Nkemnacho’s “Olukumi Kingdom” and articles in local

newspapers have documented the history of the Odiani people, bringing scholarly and

public attention to their heritage.

Today, community memory is also curated through digital media. Facebook pages, cultural

blogs and local forums share Odiani stories, songs and language lessons. Community

events emphasize traditional knowledge, and some families maintain oral genealogies

tracing their lineages to the original Yoruba migrants.

This oral tradition is not fixed but dynamic. It accommodates changes in language, religion

and governance while maintaining the core narrative of Odiani as a Yoruboid-speaking

people who adapted to a changing regional environment. The Odiani case affirms that

cultural identity is not singular, but layered and continuously negotiated

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

The history of the Odiani clan offers a window into the processes of migration, contact and

adaptation that define Anioma. Emerging from Yorubaland, shaped by Benin encounter and

embedded in an Igbo-speaking region, the Odiani illustrate how historical identities are

formed and transformed across generations.

They are not simply Yoruba exiles nor Igbo converts, but a community that carries

elements of both, reshaped by place and time. Olukumi, their language, remains a fragile

but vital marker of this history. Their governance structures, religious practices and

festivals reflect a shared heritage that is at once distinctive and interconnected with the

broader Anioma experience.

Understanding the Odiani in this way enhances our appreciation of Anioma as a frontier

region where identity is not fixed, but continuously constructed through encounter,

negotiation and cultural memory.

𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬

Aluko, B. (2010, 2015, 2022). Olukumi people of Delta State and their Yoruba origins.

Nigerian Tribune (various reprints and online editions).

Bamgbose, A. A. (1966). A grammar of Yoruba. Cambridge University Press.

(Referenced for comparative Yoruboid linguistic classification relevant to Olukumi.)

Beier, H. U. (1953). Notes on the Olukumi people of Western Nigeria.

(Unpublished field notes and linguistic observations, cited in later ethnolinguistic

studies.)

Esogbue, E. (2016). Anioma history and ethnographic notes.

(Online cultural essays and regional history blog posts.)

Nkemnacho, G. (2024). Olukumi Kingdom: History, language and identity of the Odiani

people.

Self-published monograph, Ugbodu.

Nwoye, G. (2008). Language contact and shift in border communities of Delta State.

Journal of West African Linguistics, 35(2), 45–68.

Ohadike, D. C. (1994). Anioma: A social history of the Western Igbo people. Ohio

University Press.

Talbot, P. A. (1926). The peoples of Southern Nigeria.

Oxford University Press.

(Referenced for early colonial observations of Anioma and neighboring Edo–Igbo frontier

zones.)

Ugbodu Traditional Council. (2022). Olukumi–English Dictionary Project and New

Testament Translation.

Community publication and launch materials.

Ukwu-Nzu Palace Records. (1974). Coronation and lineage records of the Obi of Ukwu

Nzu.

Unpublished palace archives.

Oral interviews and community accounts from:

• Ugbodu

• Ukwu-Nzu

• Ubulubu

• Idumu-Ogo

• Ugboba

• Ogodor

Adim Abuah

Software Developer, Writer

No comments yet.